One of the aims of this site is to describe how high-end sushi shops in America might compare to a similar experience in Japan. In my view, these similarities are growing at an increasing pace, but there are several core differences between US and Japanese restaurant culture that are worth noting.

Most important is the fact that American restaurant culture focuses on pleasing as many people as possible, whereas Japanese restaurant culture tends to focus more on specialists who are experts at one type of food. In light of this, it is not surprising that many American Japanese restaurants will offer sushi, tempura, udon, and soba on the same menu, all of which are considered very distinct cuisines (and would be found in separate restaurants) in Japan. This difference filters through to not only the layout of restaurants, but also the types of meals that might be offered to diners and the pacing of these meals.

Many high-end sushi restaurants in America offer meals that resemble more closely kaiseki feasts than a typical Japanese sushi meal. This is perhaps out of fear that American diners might find a sushi-centric meal too boring or (more likely) that many American restaurants don't have the supplier connections, chef experience, or budget to support a sushi-only omakase. Other American sushiya (most famously, Sushi of Gari) use non-traditional flavor and seasoning combinations with sushi as a way to attract American palates, utilize local ingredients, and make the most of a more limited variety of offerings (mentioned below as "new style" sushi).

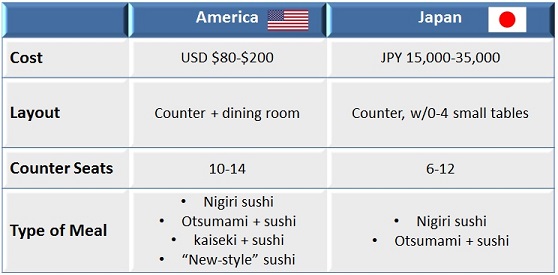

I've tried to summarize some of the core differences between an American and Japanese high-end sushiya below:

The most notable difference above is the fact that high-end Japanese sushiya are, at current exchange rates, roughly double the cost of the highest-end places in America. This reflects a few things: 1) the lower number of seats and turnover in many of these establishments; 2) an inflexibility and "need" for these shops to always pay top dollar for seasonal items and; 3) a greater emphasis on prestige of these restaurants, which allows them to command a premium price (Jiro's son, for example, only charges 2/3 the price of his father's restaurant for a similar meal). With a price differential this large, it also shouldn't be surprising that quality of ingredients and consistency of most high-end sushi in Japan is a level above the high-end sushi in America.

At this price level, it goes without saying that a typical Japanese person rarely (if ever) experiences sushi at this high level, so in some ways this is not a fair comparison to a "typical" sushi experience in Japan. Frankly, most sushi in Japan is consumed in train stations, "fast food" environments, and via takeout, just like in the US - though the quality at this more pedestrian level in Japan is much, much higher than in America.

One last point: there is a marked difference between the experience at the sushi counter (or "bar") and in the dining room at any of the establishments I write about here. In Japan, this difference is always explicit, as different menus will be offered at tables where the full chef's omakase will only be available at the counter. In America, this difference is sometimes blurred but eating at the counter will always be a better experience for a number of reasons.